From gold recycling to urban mining

Gold facts & figures 21.01.2021

Gold is one of the rarest elements on earth, and mining the precious metal is extremely costly. Demand for gold, however, steadily increased over the last decades. Of the approximately 200,000 tonnes in circulation worldwide today, in the form of jewellery or an investment, two-thirds were mined since 1950. The current rate of gold production is 3,000 to 3,500 tonnes annually. According to the U.S. Geological Survey’s 2019 annual report, what is left of the earth’s commercially mineable gold reserves will likely be exhausted within the next 15 years. There are further reasons why gold recovery is becoming increasingly important. The ecological footprint of traditional gold mining is enormous, with the general burden on the environment and the use of highly toxic substances such as cyanide and mercury, in addition to the vast energy consumption and the resulting carbon emissions. During the production of one kilo of gold, between 12 and 16 tonnes of carbon dioxide are released, even under the best circumstances, when state-of-the art, environmentally friendly technologies are applied.

Recycled gold has a much smaller carbon footprint. The production of one kilo of scrap gold results in carbon emissions of 53 kilograms, less than one-twentieth compared to traditional mining. While up to 100 per cent of scrap gold is now recycled, many other sources of recyclable gold still remain largely untapped, leaving enormous potential for optimisation.

Promising approaches for more sustainable gold extraction

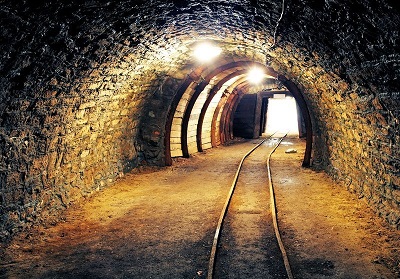

Gold is still primarily extracted through industrial mining, which necessitates disruptive procedures such as controlled detonations, clearing of forests and damming of rivers. Since most of the largest gold mines are operated in regions such as in South Africa, China or Russia, where conservation has been a long-neglected issue, the efforts to achieve more sustainability are still relatively new.

Gold is still primarily extracted through industrial mining, which necessitates disruptive procedures such as controlled detonations, clearing of forests and damming of rivers. Since most of the largest gold mines are operated in regions such as in South Africa, China or Russia, where conservation has been a long-neglected issue, the efforts to achieve more sustainability are still relatively new.

The Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) is taking important fist steps in this direction. An association of international companies and trade associations in the gold and diamond industry, the RJC stands for conflict-free, or Fairtrade, gold. In 2005, the RJC introduced a certification granted only to gold-producing companies that comply with very specific standards, which include an ethical, socially and environmentally compatible corporate policy observing human rights principles along the entire supply chain. So-called code-of-practice and chain-of-custody certification audits are carried out every three years to ensure ongoing compliance with the standards. Many major gold-producing companies are now certified.

Other promising approaches aim to completely replace environmentally harmful substances with non-toxic ones to dissolve the gold out of the ore. For example, the use of jig water propulsion plants and concentrator centrifuges based on the Knelson principle can eliminate the need for cyanide in industrial gold mining altogether. A jig concentrator is a device that separates the particles in the ore with the help of pulsing water. The Knelson Principle is the fully automated separation of minerals based on their respective specific gravity using a concentrator centrifuge. In 2019, the Australian research organisation CSIRO also brought a professional method of gold extraction to application maturity with its “Going for Gold” project, which replaces cyanide with the sulphur compound thiosulphate, a substance much more environmentally friendly.

Small-scale mining and gold panning today can also do without highly toxic mercury, and if used, there are effective measures to prevent it from seeping into the soil. So-called retorts can reduce environmental pollution by 99 per cent. Retorts are closed systems that collect the evaporated mercury when the mercury compounds are heated.

Another innovation, the so-called Wilfley process, makes it possible to completely forego poisons in small-scale mining. It uses fully automated shaking tables that process pre-concentrates from rock mills and concentrator troughs, separating the valuable mineral components from the rock. These innovative approaches, which will no doubt see further development, are paving the way for more environmentally friendly gold mining practices. Still, they will probably never be as climate-friendly as modern recycling methods – especially with regard to carbon emissions.

Gold recycling: a sustainable alternative to traditional mining

Gold is scarce, but it is also a highly sought-after precious metal, not least due to its dual function as a valuable raw material and financial investment in the form of coins or bars. And of course, gold no longer in use is not disposed of; it is recycled. The history of gold recovery goes back as far as our appreciation of the precious metal. Its simplest form is recycling old gold, for example from jewellery, coins or dental fillings. The share of recycled gold in total production has been on a slow but steady rise for many years and now accounts for more than a quarter of the annual world market supply. However, this development is not entirely linear, because gold recovery to a large extent depends on the respective gold price. While the share of recycled gold in the total supply was between 25.2 and 27.3 per cent in the last three years, it reached its highest level thus far in 2009, at 42 per cent. This was due to two coinciding major motivators for gold owners to sell their scrap gold – on the one hand, the desire for more liquidity following the financial crisis, and on the other, the high gold price, which made the sale of scrap gold particularly attractive. Accordingly, the willingness of gold owners to sell recyclable scrap gold also seems to be crucial to the share of recycled gold in global market supply. The decisive factor, however, is how easy or inexpensive it is to process the scrap gold on offer.

Gold recovery: the most common methods and processes

Scrap gold rarely has a purity of 999.9/1000, as is the case with fine gold in bar form. Jewellery gold in Europe is often a 14 carat alloy, i.e. a purity of 585/1000 and a fine gold content of 58.5 per cent. To recover pure fine gold from old gold through recycling, it must be separated from the other components of the scrap gold, mostly other metals or plastics.

The most widespread modern recycling technique is electrochemical recovery from anode slime, in which the precious metal is separated via electrolytes and without the aid of environmentally harmful substances such as mercury or cyanides. This method is also commonly defined as electrolytic refining (purification).

For gold recovery from alloys, the wet chemical or digestion process is also frequently applied, in which a separation is first carried out with Aqua Regia, the only acid capable of dissolving gold. The resulting substance is then reduced with sulphur dioxide and finally isolated through electrolysis.

A further method of gold recovery is pyrolysis, in which an incineration of the gold-bearing material at high temperatures is followed by melting.

These methods are often preceded by mechanical processing to prepare the gold-bearing material for refinement by shredding, grinding and sieving them to generate a homogeneous structure. All of the above methods have proven to be cost-efficient and environmentally friendly, especially when recycling scrap with a high gold content, such as dental gold. The situation is different for gold recovery from sources with a very low gold content.

Urban mining: How scrap is turned into gold

While old gold jewellery, dental gold and gold from industrial plants is fully recycled today, only about 15 per cent of the gold recovered from so-called electronic waste is thus far commonly recycled. This approach seems outdated, as the same amount of gold can be recovered from recycling 40 smartphones as from one tonne of ore from a gold mine. One tonne of PC circuit boards contains more than 100 grams of gold. Around 440 tonnes of gold are currently incorporated in the automotive parts of 260,000 vehicles across Europe, and very few of them enter the recycling circuit when the time comes for them to be scrapped. According to Gold.info, an information platform for precious metals, gold at a current value of roughly €3.7 billion thus remains unused and is routinely shipped to emerging countries as worthless electronic scrap.

While old gold jewellery, dental gold and gold from industrial plants is fully recycled today, only about 15 per cent of the gold recovered from so-called electronic waste is thus far commonly recycled. This approach seems outdated, as the same amount of gold can be recovered from recycling 40 smartphones as from one tonne of ore from a gold mine. One tonne of PC circuit boards contains more than 100 grams of gold. Around 440 tonnes of gold are currently incorporated in the automotive parts of 260,000 vehicles across Europe, and very few of them enter the recycling circuit when the time comes for them to be scrapped. According to Gold.info, an information platform for precious metals, gold at a current value of roughly €3.7 billion thus remains unused and is routinely shipped to emerging countries as worthless electronic scrap.

Why, then, is this potential left largely untapped? After all, consistent gold recovery could make industrialised countries with limited gold deposits of their own less dependent on weightier gold-producers such as China or Russia. On the one hand, this is due to the comparatively high cost of recycling electronic waste, and on the other, due to the lack of sustainability. While the recovery of gold from smartphones and PCs is entirely free of environmental toxins, it consumes an enormous amount of energy, leading to high carbon emissions and thus, a less favourable ecological track record.

Is the production of green gold from e-waste even possible? It certainly will be, with an innovative approach that cuts urban mining energy consumption in half. Instead of melting down circuit boards from smartphones and PCs, gold can be extracted via microbes. According to information published by Brain Biotechnology AG, it will be a while before this method can be applied to all forms of electronic waste, as it requires, among other things, extensive modifications to established recycling structures.

The bottom line: gold recycling is on a track to success

The ecological footprint of gold has decreased significantly in recent years. Besides more environmentally friendly mining methods, it is gold recovery that is making the precious metal greener, a trend that will be amplified as urban mining options are further explored. This is important for environmental reasons and also takes into account the wishes of a growing number of investors who seek to invest sustainably while benefitting from the portfolio-stabilising effect of gold.

Arnulf Hinkel

Financial journalist

Xetra-Gold Hotline

Do you have questions? We have the answers. Contact us here: 9 a.m.–6 p.m. CET

xetra-gold(at)deutsche-boerse.com

For press inquiries: media-relations(at)deutsche-boerse.com